Dark History: The Case of Margaret “Peggy" Mortimer

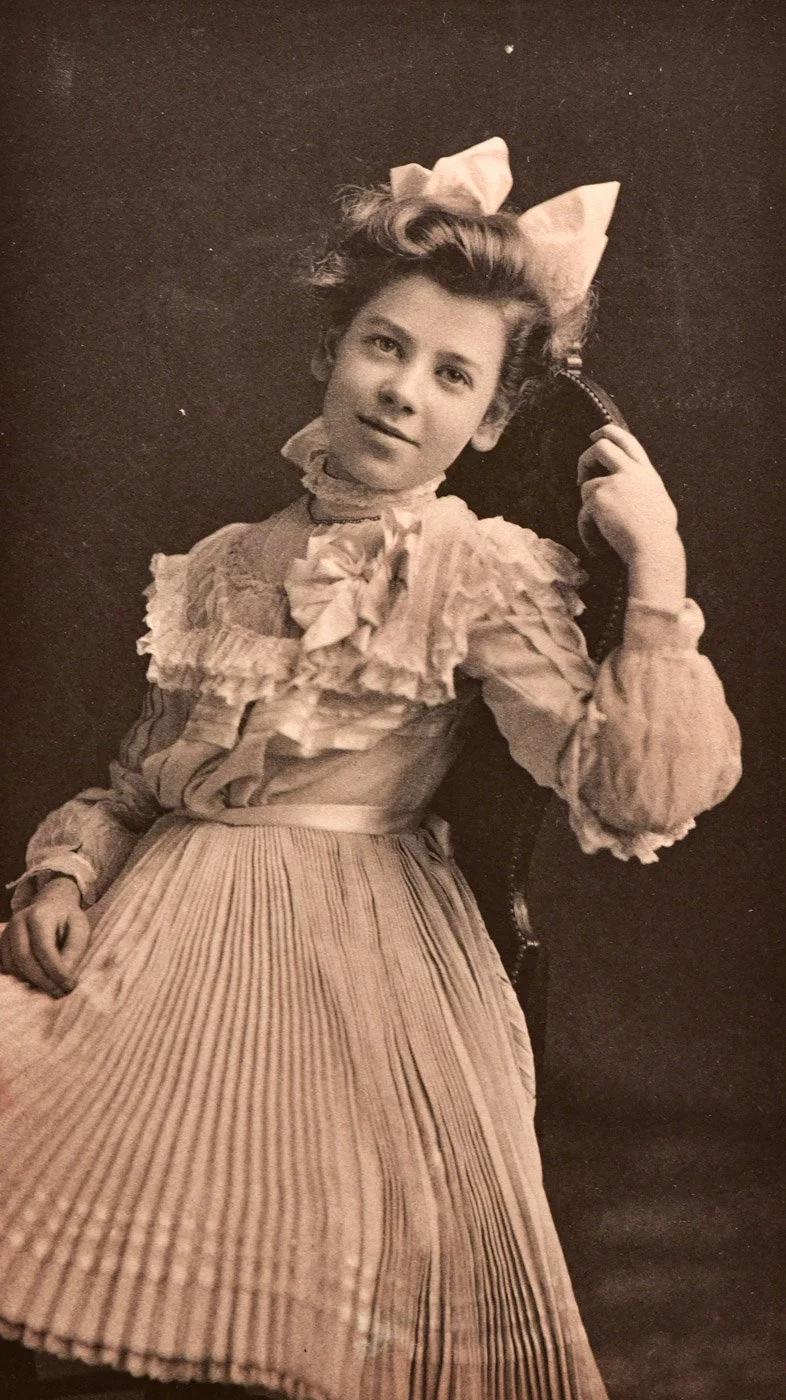

Margaret “Peggy” Mortimer in an Atlantic City Photo Booth (Family archives, digitized by Murder, She Told)

Peggy and Bert Mortimer: Woven into the Fabric of Mexico, MO

Margaret Rhodus, who went by Peggy, was born in St. Louis in 1891. Her early childhood moved in step with her father, Birch Rhodus’s, business career—first to Chicago, then to New York, and eventually to Mexico, Missouri, where he would become president of the Continental Bank Supply Company. From a young age, Peggy was encouraged to explore music and the arts. She was a trained soprano who studied voice seriously and remained devoted to music throughout her life.

Albert S. Mortimer, known to most as Bert, was born on December 5, 1885, in New York. By the mid-1910s, he was practicing law in New York City. A staunch Democrat, Bert cultivated friendships that extended into political circles, including close ties with Missouri Governor Lloyd Stark and former New York Governor Alfred Smith.

In 1916, while visiting Atlantic City, he met Peggy through a mutual friend. Peggy, her sister, and her mother were living there at the time. Bert and Peggy developed a connection and a courtship soon followed. They married two years later, in 1918, in a Catholic ceremony that reflected Bert’s faith. After their wedding, Bert remained in New York to continue his legal career, while Peggy spent extended time in Missouri with her family—leading to some speculation about the state of their marriage, though Bert would later insist those concerns were unfounded.

In 1926—eight years into their marriage—Peggy persuaded Bert to make the move to Mexico. She had lived there for 6 months with her family, helping to care for her mother without him. He left law behind and took a position as office manager at the Mexico Bank Supply Company, where her father served as president.

They moved into a stately two-and-a-half-story Victorian home at 927 South Jefferson Street—the former residence of the president of nearby Hardin College. With its white clapboard siding, broad wraparound porch, and steep gabled roof, the house was more than a residence, it was a landmark—a reflection of the Mortimers’ social standing. They lived there with Peggy’s parents, both of whom were in declining health, and whom Peggy helped care for with quiet devotion. Though she and Bert had no children, the house rarely felt empty. It was a welcoming place, often filled with visiting friends and relatives. During the holidays, the rooms came alive with music drifting from the parlor, the smell of baked ham from the kitchen, and the sound of laughter rising through the halls. Bert later said of their marriage, “We never had a single quarrel all our married life, not even a lovers’ spat.”

She was a member of the Monday Music Club and sang regularly with the choir at Mexico’s Methodist Episcopal Church. She was described as an “attractive brown-haired woman, about 5 feet 6 inches tall, weighing about 130 pounds,” and was considered “one of Mexico’s most prominent and charming women.” In 1936, at age 45, Peggy stepped into a new role—appearing in a local theatrical production for the town’s Thanksgiving program. The one-act comedy, Suppressed Desires, was staged at the McMillan School and featured just three performers. Peggy played the lead role of Henrietta, delivering fast-paced lines in a satire of amateur psychoanalysis. The director of the show was her husband Bert.

For the Mortimers, Mexico, Missouri offered rhythm and stability. Peggy immersed herself in the cultural life of the town, while Bert focused on business and civic responsibilities. Their presence was steady. Their roles were well-established.

As Thanksgiving approached in 1937, the Mortimers were preparing—as they had many times before—to host family, welcome guests, and mark the holiday season with music and tradition. There were no warnings. No signs that anything was amiss. The season had just begun.

And it would be their last together.

Just Ten Blocks

It was just ten blocks.

On Wednesday, November 24, 1937, the eve of Thanksgiving, Peggy Mortimer stepped out of Marlow’s Drug Store and made her way toward Gentle’s Newsstand. The sun had set at 4:47 PM, and by 6:00 PM, the temperature had dropped into the mid-40s, carried by a stiff, biting wind. Peggy had spent the afternoon in Mexico’s downtown square, running errands and preparing for the holiday. A box of candy, some artificial flowers, a bottle of Odorono (an antiperspirant), a few magazines, and a gift picked up for her mother—all tucked into the crook of her arm as she walked.

A familiar figure in town, she’d been seen chatting with friends in front of Scott’s Store and browsing at Pilcher’s Jewelry.

At around 6:10 PM, Peggy passed the Hoxsey Hotel on South Jefferson Street, just a few blocks from her home.

At that same time, sixteen-year-old Ama Potts, was also on her way home from her job at a local drug store. For much of the walk, Ama was behind Peggy, however, she passed Peggy just a few hundred feet from the Mortimer home. Ama may have heard the jangle of the 14 interlocking bracelets that Peggy was wearing as she passed.

When Ama was half a block from the Mortimer house after passing it, she heard a scream, sharp and sudden. Then another, muffled, like someone had clamped a hand over the sound. Then three muffled thuds. She didn’t look back. Frightened, she ran.

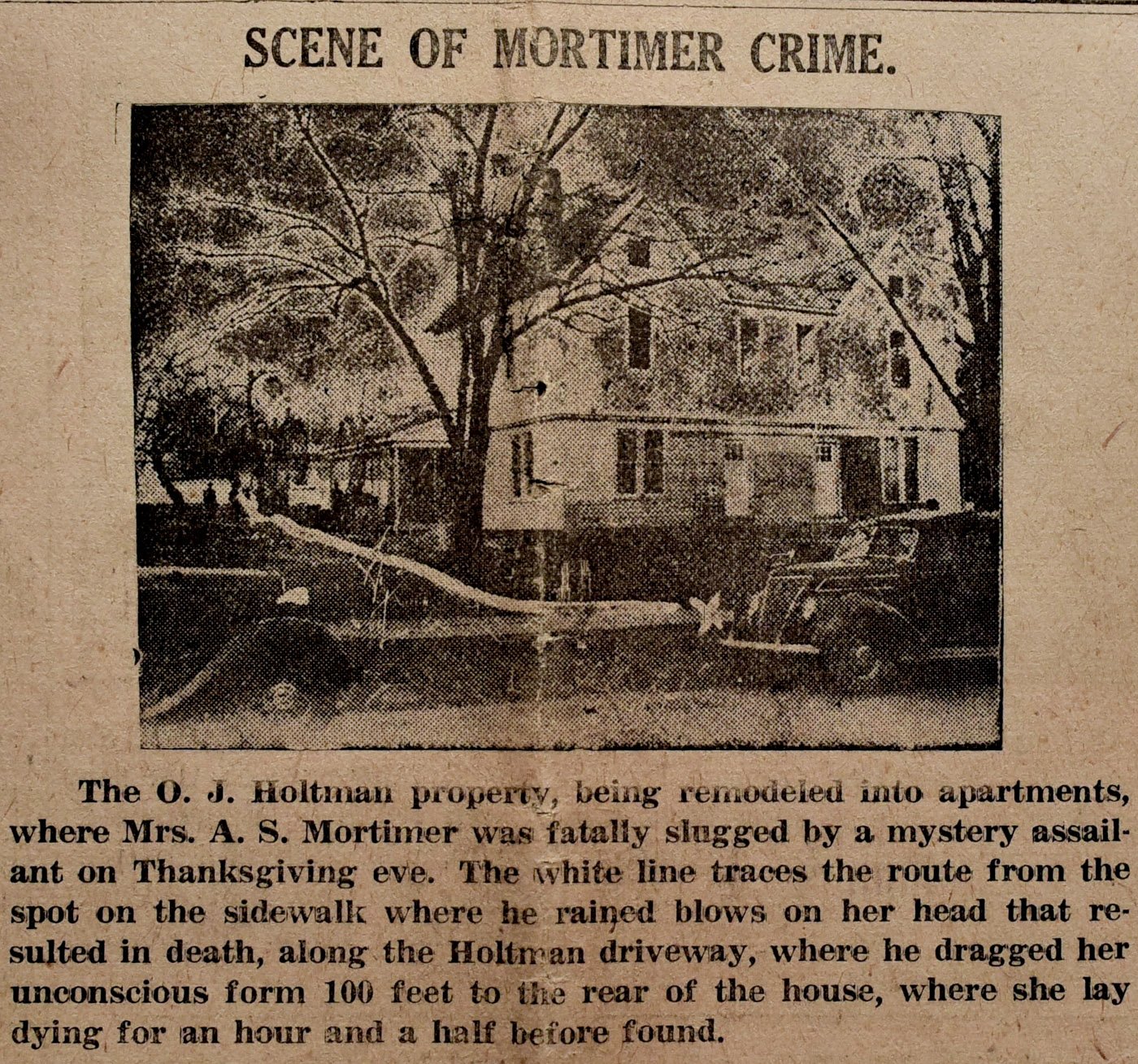

Just 125 feet from her front door, Peggy was attacked. She had reached the sidewalk in front of the Holtman house—a partially constructed property, darkened and empty, just next door to her residence. There, in the shadows of her own neighborhood, she was struck—three times, at least—with a force that left her unconscious.

Back at the Mortimer home, Bert was entertaining holiday guests—Mr. and Mrs. Irwin of San Diego, California. He had returned from work earlier that evening with his father-in-law, B.F. Rhodus, who had been away from the office due to illness. After a brief conversation, Bert went upstairs to dress for dinner, which was to begin at 7:00 PM. He asked the maid whether Peggy had returned, but didn’t express concern., figuring that she was still rehearsing for an upcoming performance. At 7:10 PM, with no sign of her arrival, they began the meal without her.

At 7:45 PM, their neighbor O.J. Holtman visited the vacant property he owned next door. He and his son, Orvid, walked through the house. Out back, Orvid heard a sound—faint and pained—possibly a voice. They stepped outside and saw a body.

Orvid ran to a neighbor’s home to call for help. O.J. flagged down passing boys and sent them to the Mortimer house for help.

When the two boys arrived at the Mortimer home asking Bert for assistance, he immediately grabbed a pair of flashlights and ran in the direction of Hardin Hall, which was in the wrong direction. Bert’s initial thoughts were that one of the boy’s playmates was injured hunting pigeons in the abandoned Hardin College campus. One of the boys corrected him saying, “No, it’s over this way,” and directed him to the Holtman property.

Bert would later describe the following moments, saying,

“As I came to the driveway, I turned the light on the ground and saw some magazines and a woman’s hat. I recognized it as my wife’s. I asked where she was and then flashed my light to the rear [of the house]. I saw a body and ran over and found my wife, lying on her back with her feet drawn up. Her stockings were torn and her clothing pulled up over her shoulders and head. Her face and head was covered with blood. I took a handkerchief from my pocket and wiped her face to determine how badly she was hurt. When I touched her, she threw her arms about wildly as if fighting off an assailant.”

She couldn’t speak, and she didn’t seem to recognize him. Peggy was transported by ambulance to Audrain County Hospital.

She never regained consciousness.

At 1:15 AM, in the early hours of Thanksgiving Day, Peggy Mortimer succumbed to her injuries and passed away.

It was just ten blocks—a short walk home—but she never made it.

The Investigation into Peggy Mortimer’s Murder

By the wee hours of Thanksgiving morning, Thursday, November 25th, the investigation into Peggy Mortimer’s murder had formally begun. While neighbors and her own family were the first to discover her body, officials were soon brought to officially document and process the scene.

Peggy had been found lying on her back in the rear yard of 911 South Jefferson Street—a partially constructed property just 125 feet from her own front door. Officers noted the positioning and condition of her body in detail. Her black crepe dress and silk slip had been pulled up to her chest. Her silk step-in undergarment was torn and discarded nearby, while an elastic girdle, still clipped to her stockings, remained in place. There were no stab wounds or gunshot wounds. Her jewelry—two rings and a bracelet—was still on her body, leading officers to believe robbery was unlikely to be the motive.

While there was no report of semen, investigators believed that an attempt at sexual assault had been made—her undergarments were torn, her clothing was disarranged, and her body was moved from the sidewalk into a more secluded area—all signs consistent with what authorities then-termed “criminal assault.”

A few feet from where Peggy was found, officers recovered a piece of stove wood—a roughly-cut piece of white oak commonly used for heating—approximately 14 to 15 inches long and about 3 inches in diameter. It was stained with blood and was dotted with fragments of felt from Peggy’s hat. Investigators concluded it had likely been the weapon used in the attack. The stove wood was believed to come from the home of Miss Maude Wallace and Mrs. W. H. Wallace, a few blocks north. The wood didn’t match other wood on the Holtman property—it was the “only one of its kind.” The muffled thuds that Ama heard were likely the blows delivered to Peggy’s head. Drag marks on the ground indicated Peggy had been assaulted on the sidewalk, then dragged roughly 100 feet into the dark yard.

Given the brutal nature of the attack, the fact that her body was moved, and the close proximity the killer had to have with her body, police believed that he had to have gotten blood on him and his clothing. Laundromats were put on notice to be on the lookout for any bloody clothing.

Scattered across the front of the yard were Peggy’s belongings from that evening: magazines, a box of candy, artificial flowers, and a bottle of Odorono antiperspirant. A single shoe, a bloody handkerchief, and her hat were also recovered. All items were collected and sent to the Missouri Highway Patrol laboratory in Jefferson City for fingerprint analysis.

Medical staff at Audrain County Hospital documented Peggy’s injuries. Dr. Paul Coil identified a long gash about 4½ inches in length that penetrated the skin of her scalp and revealed the bone of her skull. X-rays confirmed that her cranium was fractured. Also on her head were two smaller contusions (or bruises) about 2-3 inches in length. The medical examination revealed that Peggy’s left ankle was bruised and swollen and there were contusions on the left shinbone and left hip. The abrasions on her hip were believed to be the result her body having been dragged. There was a maintained path from the sidewalk to the rear of the property and it was made with cinder—the black sooty remains from burnt coal, an inexpensive and ubiquitous material commonly used in landscaping for making a simple path. The sharp cinder pieces cut into her skin.

The nature of the wounds indicated multiple blows delivered with considerable force. Peggy’s cause of death was officially listed as cerebral hemorrhage due to a fractured skull.

Although Peggy survived for nearly six hours, she never regained consciousness—never revealed any clues about who had attacked her.

Attention turned next to the physical environment. The location where Peggy was found was especially dark. A streetlight, two houses north of the Holtman property, was out, leaving that stretch of South Jefferson Street poorly lit. Likely because of that darkness, by the time that the Peggy was discovered, one or more people had already walked through the pool of blood on the sidewalk and tracked the blood both directions from its location. Behind 911 South Jefferson were piles of discarded lumber, broken bricks, and overgrown garden plots—offering ample hiding places. Across the street loomed the abandoned Hardin College campus, its unlit buildings and tree-lined grounds stretching over a deserted acre.

Investigators pieced together an early timeline based on witness accounts and observed details. Peggy was last seen walking south on Jefferson Street just after 6:00 PM, her arms full of small purchases from downtown shops. Sixteen-year-old Ama Potts had passed Peggy on foot near the homes of Dr. Bragg and Sam Bishop, just a few hundred feet before the Mortimer residence. Moments later, as Ama reached the front of the Mortimer home, she heard two sharp screams. She ran without looking back.

Ama Potts ran the remaining blocks to her home at 1514 South Cole Street and told her mother what she had heard. The family did not report it immediately, later explaining that there was no telephone in the house. It was also reported that Ama’s mother didn’t believe her daughter’s story. This, in part, was to blame for the roughly 1.5 hours between the attack at 6:15PM, and the discovery, which didn’t occur until 7:45PM. According to other newspaper accounts about this crucial witness, a member of her household eventually went downtown to notify police only to discover that the assault had already been reported and was under investigation.

From the outset, police believed Peggy had been struck from behind with the piece of stove wood as she neared home, likely on the sidewalk in front of 911 South Jefferson. Investigators theorized that the killer had hidden behind a tree near the sidewalk, watching and waiting. Moments earlier, sixteen-year-old Ama Potts had passed the same spot, unknowingly walking within feet of the concealed attacker.

Had Ama not overtaken Peggy just before the attack, officers later said, she might have been the victim instead. They believed the assailant had deliberately let Ama pass, waiting for the woman behind—Peggy—who was presumably alone. After the initial blows, the killer appears to have paused, watching Ama flee, seeing if she might raise alarm. The pool of blood that collected on the concrete at the site of the initial blows suggested Peggy was already gravely injured at that point—bleeding and unconscious—while her attacker stood nearby, assessing the risk.

Only once Ama had disappeared from view did the killer drag Peggy into the dark, vacant yard. Her underclothing was torn, her dress disarranged.

Officers also noted one detail that suggested the attacker may have been interrupted. It was a theory that actually came from Bert. Around the same time as the attack, James Irwin, the Mortimer’s houseguest, had moved his car, which was parked around the corner, and attempted to maneuver it into the garage behind the Mortimer house. As he did so, the headlights from his vehicle would have shone into the rear yard where Peggy was found. It was night time—the sun had been down for hours. Police believed those lights may have startled the attacker, prompting him to flee before he could finish whatever he had intended.

Bloodhounds were brought in from Fulton, Missouri, a town about 20 miles away, by 10:00 PM. By then, a large crowd had gathered at the scene, trampling footprints and other subtle potential clues. The mix of people had also introduced myriad competing scents, and no clear trail could be established.

By mid-morning Thursday, the Missouri Highway Patrol, under Col. Marvin Casteel, had assumed leadership of the case. State patrol officers worked alongside Mexico police and Audrain County officials to process evidence, interview witnesses, and begin a more structured investigation.

What was clear from the start was that Peggy Mortimer’s murder had been brutal, targeted, and committed astonishingly close to home. Yet as Thanksgiving Day unfolded, no suspects were named, no arrests were made, and no one could yet explain how—on a chilly, windy evening—Peggy Mortimer’s walk home had ended in such violence just steps from her front door.

The Aftermath

As winter turned into spring and 1938 gave way to a new year, the urgency surrounding Peggy Mortimer’s murder began to fade. The reward fund remained unclaimed. Newspaper headlines turned to other stories. And after Ira Cooper returned to St. Louis, the investigation lost some of its momentum.

What had once dominated the town’s attention became a quiet undercurrent. On Jefferson Street, near the place where Peggy had been killed, neighbors were wary. Mothers warned their daughters. People chose new routes home after dark. The flowers neighbors had placed at the edge of the lawn in Peggy’s memory on 911 South Jefferson eventually withered.

Peggy’s family pulled back from public view. Her husband, Bert, remained in Mexico. In the years following her death, his public presence faded. Mentions of him in local newspapers dwindled. He never remarried. He made no further public statements about the case. Whatever thoughts Bert carried, he kept them to himself.

Bert Mortimer’s own story ended in a way that only deepened the sense of mystery. In the summer of 1953, nearly sixteen years after Peggy’s death, Bert boarded a train to New York. He said he was going to a funeral, but he never arrived. Days later, authorities in New York found a man—unconscious, unidentified—collapsed on a city street. He died in the hospital without waking. It wasn’t until weeks later that Mexico police were contacted. The man had carried no identification, but someone eventually made the connection—it was Bert. He’d suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on August 31. He was 67 years old.

For a time, Bert was buried in an anonymous grave in New York City. Only later did his family claim his body, arrange for its exhumation, and return it to the family plot.

Peggy’s case was never closed, and by the time Bert died, few believed it ever would be. The records grew dusty. The details slipped into memory. What remained was the space where resolution should have been—an empty page at the end of a long, grim chapter.

Peggy’s death was unavenged—a woman of music and grace, taken without warning, without justice. In life, she was a fixture of her town, known for her voice, her kindness, her presence. Even now, nearly a century later, it’s worth remembering not just how she died—but who she was, and what was unfairly stolen. She was never given the chance to live the full shape of her life. And the silence left behind—that’s what remains the most unbearable of all.

Continue Peggy’s story: Listen to the podcast episode. This text has been adapted from the Murder, She Told podcast episode, Dark History: The Case of Margaret "Peggy" Mortimer. To hear Peggy’s full story, find Murder, She Told on your favorite podcast platform or listen on the player at the top of the page.

Click here to support Murder, She Told.

Connect with Murder, She Told on:

Instagram: @murdershetoldpodcast

Facebook: /mstpodcast

TikTok: @murdershetold

All photos shared with us from the family’s archive have been digitized and edited by Murder, She Told

Birch Rhodus, Peggy’s father (family archives)

Esther Rhodus, Peggy’s mother (family archives)

Esther Rhodus, Peggy’s mother, middle (family archives)

Esther Rhodus, Peggy’s mother (family archives)

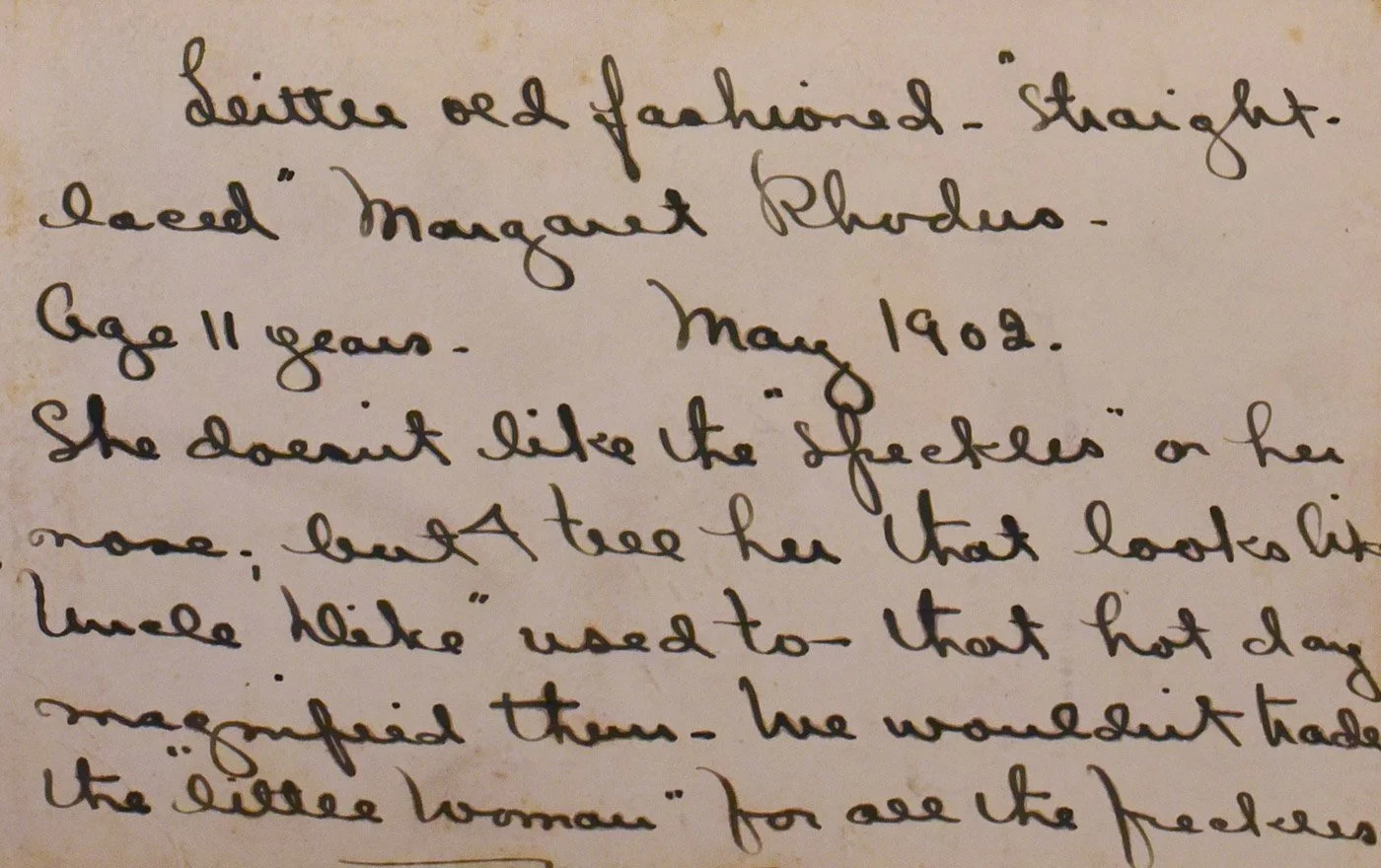

Peggy Mortimer, age 11 (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, far right (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, right, dressed for a theatrical performance (family archives)

Alice “Allie” Rhodus, age 28, St. Louis, MO (family archives)

The three Rhodus siblings, Peggy, Howard, and Allie (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, leftmost (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer (Mexico Evening Ledger)

Peggy Mortimer, left, Allie, right (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, left, Allie, right (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, left, Allie, right (family archives)

Bert Mortimer, Peggy Mortimer (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, 1936, photo booth in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, 1936, photo booth in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, 1936, photo booth in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Bert Mortimer, Peggy Mortimer, walking on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, 1936, photo booth in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, 1936, photo booth in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, 1936, photo booth in Atlantic City, NJ (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer, the weekend before she was killed, 1937 (family archives)

Peggy and Bert’s home; they lived with Peggy’s parents, Birch and Esther Rhodus; 929 South Jefferson, Mexico, MO (family archives)

929 South Jefferson, Mexico, MO (Notorious Missouri)

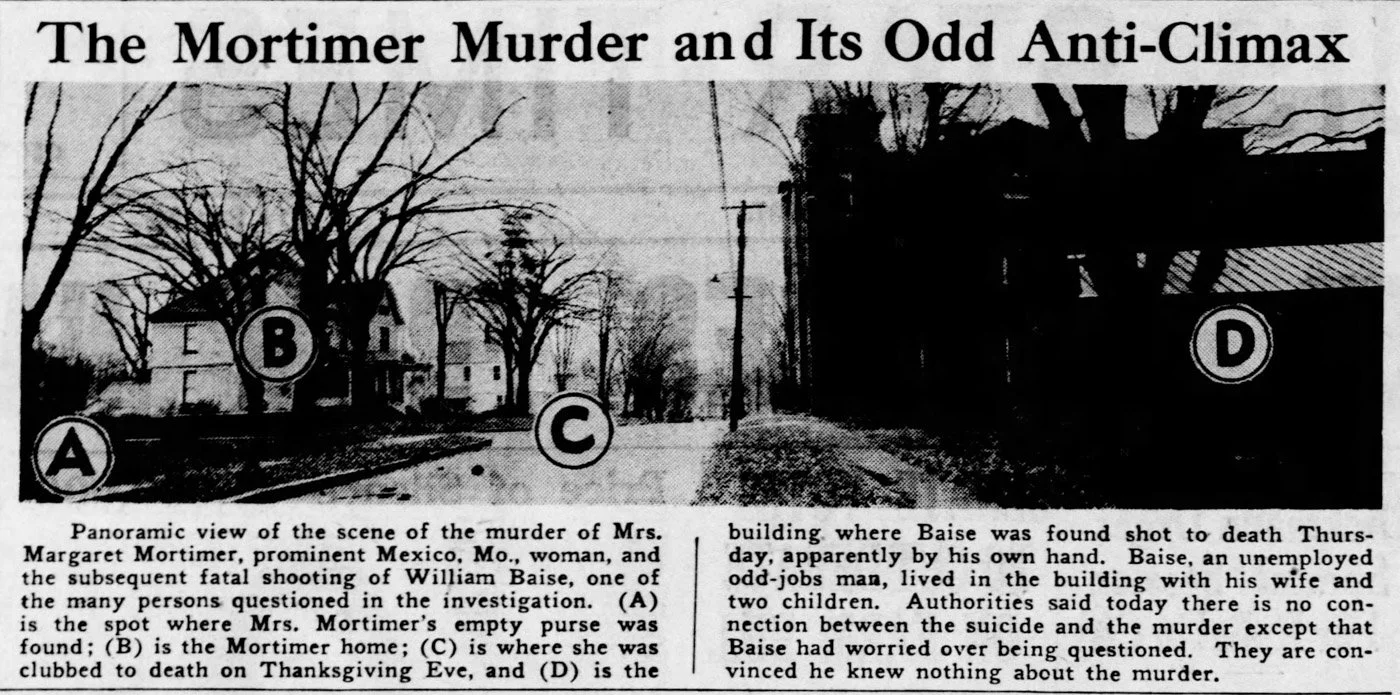

Peggy and Bert’s home on left, the Holtmans’ home on the right where Peggy was killed (Kansas City Times)

The Holtmans’ home, the crime scene of the murder of Peggy Mortimer (family

Crime scene, Peggy Mortimer (St. Louis Star & Time)

Crime scene, Peggy Mortimer (family archives)

Crime scene (Kansas City Times)

Crime scene (Mexico Evening Ledger)

Crime scene (St. Louis Star & Times)

Ama Potts, the witness who was walking with Peggy (Kansas City Times)

Peggy Mortimer, headshot commonly shared in the news (St. Louis Globe-Democrat)

Inscription on the back of a photo of Peggy when she was 11 years old by her mother, proving the year of her birth (family archives)

Peggy Mortimer open casket and flowers at her funeral (family archives)

Family headstone (findagrave.com)

Peggy Mortimer’s grave marker (findagrave.com)

(St. Louis Globe-Democrat)

(Moberly Monitor-Index)

(Daily News and Intelligencer)

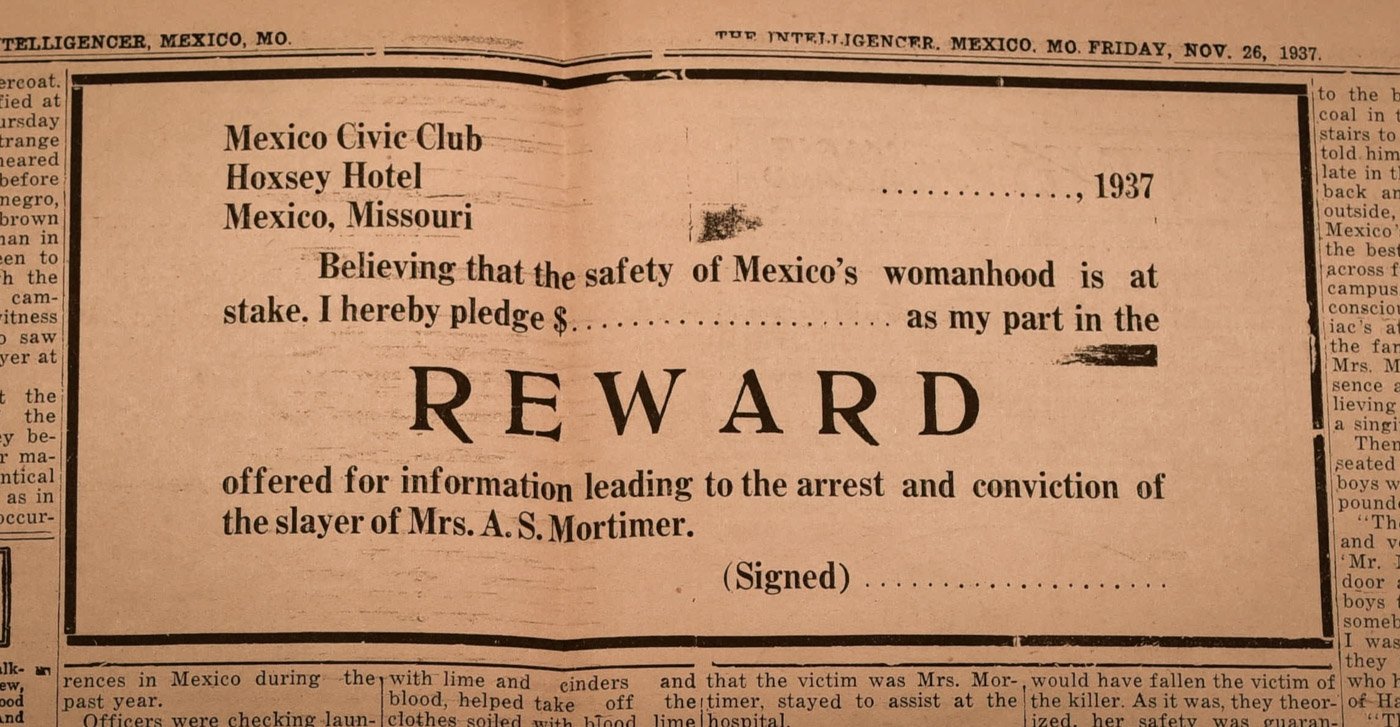

Individual contribution template letter to reward fund (The Intelligencer)

(ebay.com)

(ebay.com)

(ebay.com)

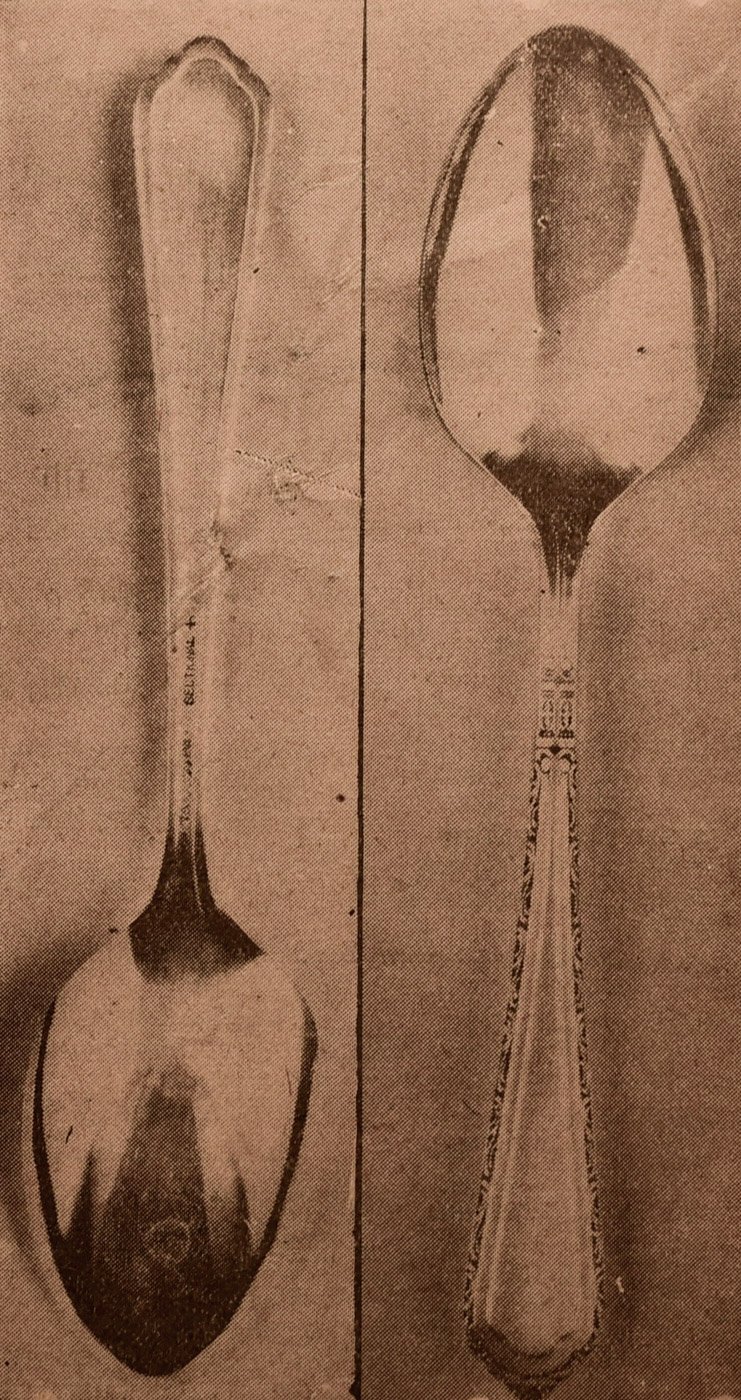

Spoons that were missing from Peggy’s person (Mexico Weekly Ledger)

Wallco Sectional spoon, Carlton pattern (ebay.com)

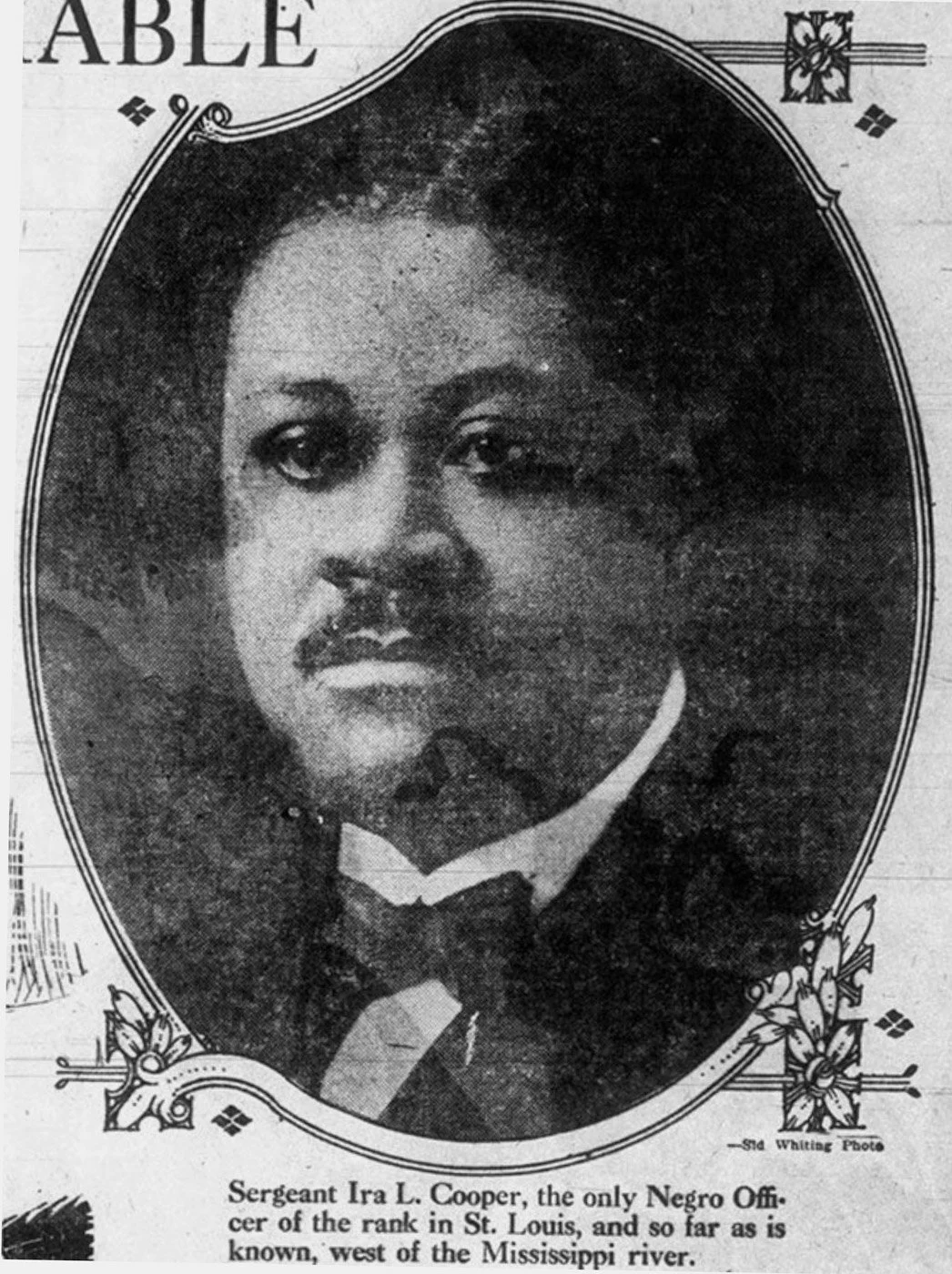

Ira Cooper (Notorious Missouri)

Ira Cooper (St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

Telegram from family searching for missing Bert Mortimer (family archives)

Birch Rhodus, Esther Rhodus (family archives)

Sources For This Episode

Newspaper articles

Various articles from Fulton Daily Sun-Gazette, Jefferson City Post-Tribune, Mexico Ledger, Mexico Weekly Ledger, Moberly Monitor-Index, Springfield Leader and Press, St. Louis Argus, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Star and Times, The Daily News and Intelligencer, The Kansas City Times, The Maryville Daily Forum, The Springfield News-Leader, The St. Louis Star and Times, and The Weekly Kansas City Star, here.

Written by various authors whose names name were not credited in any of the articles we collected.

Photos

Photos as credited above. All family archive photos have been digitized and edited by Murder, She Told.

Book

Notorious Missouri, published in 2021 by James and Vicki Erwin

Interviews

Many thanks to Anne Belden, Peggy’s great-niece.

Online written sources

'Margaret “Peggy” Rhodus Mortimer' (Find a Grave), 4/23/2014, by Martha Ann Darby Campbell

Credits

Research, vocal performance, and audio editing by Kristen Seavey

Research, photo editing, and writing by Byron Willis

Written by Ryan George

Additional research by Amanda Connolly and Kimberly Thompson

Murder, She Told is created by Kristen Seavey.